More on:

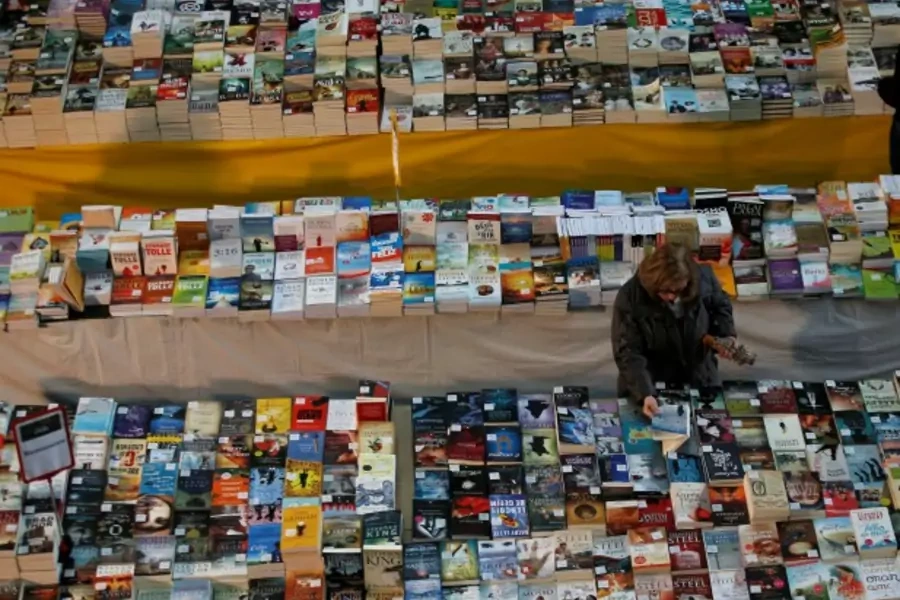

It’s that time of year again---when Washington cooks, the public transport goes on extended holiday, people head to the beach, and I offer some thoughts on books to take with you on vacation if you have an interest in Asian history, Southeast Asian politics, and Southeast Asian culture. Keep in mind that none of these books are exactly traditional “beach reads”---light page-turners that you can flip through while also watching your kids bury themselves in sand.

One recent work that I recommend highly is China’s Future by David Shambaugh, director of the China Policy Program at George Washington University. Shambaugh is always worth reading on China, but in this relatively slim new work he concisely outlines his thesis that the Communist Party is beginning to crack---that China is actually less stable domestically than many outsiders think, and that China cannot defy the trend of history by continuing to get richer without opening its political system. I don’t share Shambaugh’s certainty that the Party is entering a “protracted” demise---Beijing has proven far more resilient than many Chinese and foreign observers had thought---but the book is insightful and clear.

Another worthy new title, and one of several new works on Myanmar, is Blood, Dreams, and Gold: The Changing Face of Burma by former Economist Southeast Asia bureau chief Richard Cockett. During his time with The Economist, Cockett traveled widely in Myanmar, which was beginning to open up after decades of military rule and economic isolation. I wrote a longer review of Cockett’s new book, along with other new books on Myanmar, in the Washington Monthly earlier this year.

In short, Cockett offers non-specialist readers an overview of the many, knotted reasons why Myanmar, a country that six decades ago had built a fragile democracy and seemed poised to take off economically, collapsed into a poor, military thugocracy that lasted for fifty years. In addition, Cockett has traveled so extensively in Myanmar today that he paints a full picture of the country seemingly on the verge of democratization, following the transition to civilian rule in the early 2010s and last November’s landmark national elections. He guides the reader in teasing out why the military, so long in control and so ruthless, was willing to give up power in the early 2010s, though it remains to be seen whether the military has fully retreated to the barracks. He also offers extensive reportage from some of the most economically depressed, conflict-torn parts of the county, like remote Chin State, where foreign reporters rarely venture. Cockett is not highly optimistic about Myanmar’s prospects for democratic consolidation; he believes its insurgencies remain too deeply engrained, its army retains too much influence, and its institutions are far too weak for democracy to take strong hold.

For people who want to know more about the crisis in western Myanmar, where some 150,000 ethnic Rohingya have been driven from their homes since the transition to civilian rule in Naypyidaw in the early 2010s, I also recommend The Rohingyas: Inside Myanmar’s Hidden Genocide by Azeem Ibrahiim, a fellow at Oxford and a professor at the U.S. Army War College. The book is not the easiest to read---the prose is sometimes a bit confusing---but it is, right now, the essential guide to the ongoing, largely ignored crimes against humanity in western Myanmar. It is highly depressing material, especially considering how little pressure has been put on Naypyidaw to address the situation in the country’s west.

Finally, consider picking up A Life Beyond Boundaries, the posthumous memoir of Benedict Anderson, perhaps the most influential Southeast Asia scholar of the twentieth century. Anderson, who died last year, was instrumental in expanding Southeast Asia studies in the United States. He also played a central role in bringing the massacres in Indonesia in 1965 and 1966 to the attention of the world. For his role in producing a report, done by a team of researchers at Cornell University, on the massacres, Anderson was banned from Indonesia until the end of the Suharto regime. Anderson later wrote multiple influential books on the Philippines and Thailand, and---in 1983---gained an even wider audience with his landmark work, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism. In it, he redefined the study of nationalism, arguing that nations are socially constructed, and that these large, constructed communities were only launched by the creation of the printing press and other modern inventions. In later life, as Southeast Asia began to democratize, and shed some of the sociocultural traditions Anderson had studied, Anderson dedicated himself to disparate projects on Southeast Asian culture and religion, and the impacts of modernization. In addition, he was apparently determined to show that scholarship should never mean narrowing one’s focus too much, a point he returns to regularly in his memoir.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store