Richard Javad Heydarian is a specialist in Asian geopolitical/economic affairs based in Manila.

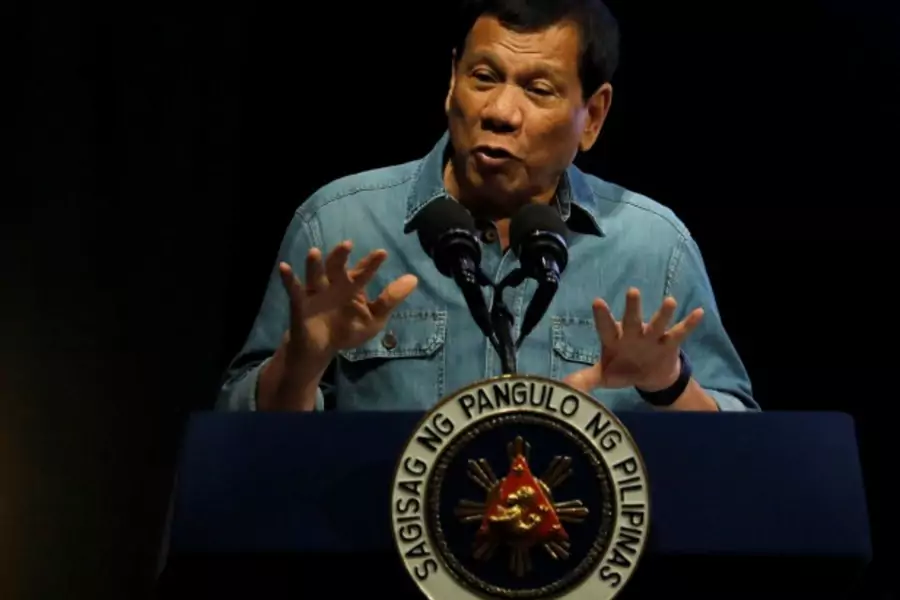

After upending Asian geopolitics over the past year, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte now is set to make his mark on the most important regional organization, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Manila has taken over the chairmanship of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations this year---chairmanship rotates annually---amid much fanfare about ASEAN. The regional body is marking its 50th anniversary in 2017 , and declaring that ASEAN is “Partnering for Change, Engaging the World.” There is hope that global leaders from dialogue partners, namely U.S. President Donald Trump, Russian President Vladimir Putin, Chinese President Xi Jinping and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo will visit the Philippines during the ASEAN summit in November.

More on:

The regional body can congratulate itself on several victories during its five decades of existence. It can justifiably look at decades of robust economic integration, which ASEAN has promoted---all leading up to the current ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), which is essentially a regional free trade agreement that cuts tariff rates on some sectors to as low as zero. (Critics charge that in certain economic sectors the AEC is not really a true free trade agreement, and allows for continued high barriers in many sectors.) In addition, since ASEAN was created fifty years ago, at the height of the Vietnam War, there have been few outbreaks of armed conflict between members of the organization.

ASEAN was launched by the five proximately positioned states of Thailand, Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines, which were largely aligned with the West and against the Communist bloc during the Cold War. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, which marked the end of ideological battles in Asia, Indochinese states, some still formally communist, of Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos, and Myanmar. (Brunei had joined in 1984, after gaining its independence.)

During the Cold War, Southeast Asia was of course a major battleground for foreign powers as well as a site for battles between Southeast Asian nations.The tempestuous years of Konfrontasi (1963–1966), saw Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia flirting with all-out military confrontation. Although there have been internal conflicts since then, like the violence in Papua, Aceh, and East Timor, the organization has worked to avoid a major regional conflict.

Now, with the AEC in place ASEAN has also set its eyes on establishing a common market. If ever truly implemented, a Southeast Asia-wide common market would facilitate labor and capital mobility enormously. It also would reduce or remove the remaining non-tariff barriers that still impede regional growth.

Yet even as it celebrates decades of successful efforts, ASEAN also is trying to solve several major diplomatic challenges in 2017. In particular, the organization is scrambling to negotiate a Code of Conduct (COC) in the South China Sea, where China and a number of Southeast Asian countries are at loggerheads over disputed land features (i.e., Spratlys, Paracels, and Scarborough Shoal), large-scale fisheries stock, and potentially vast seabed hydrocarbon and mineral resources.

More on:

The festering disputes with Beijing in the South China Sea are beginning to tear the fabric of the regional organization asunder. Operating on a notoriously slow decision-making process, where unanimity is the prerequisite for every joint statement and agreement, ASEAN has been fractured over the South China Sea. Back in 2012, during Cambodia’s chairmanship, the ASEAN leaders even failed to agree on discussing the South China Sea disputes. For the first time in its history, the regional body even failed to issue a joint communiqué during the meeting of its foreign ministers in mid-2012.

Although the Philippines historically has been one of the leaders of ASEAN, with highly competent diplomats and successful chairmanships of the organization in its past, with Duterte at the helm in Manila, the Philippine president could add to the organization’s instability. Under Duterte, the Philippines, is also in the middle of an uncertain and perilous foreign policy recalibration. Since Duterte’s ascent to presidency last year, he has called for a downgrade in military cooperation with the United States, closer Philippine ties with China, and relegation of maritime disputes to bilateral talks, rather than multilateral discussions via ASEAN. So far, he has scaled back joint military exercises and cancelled plans for joint patrols with America in the South China Sea. Though he has given the green light for the implementation of the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA), Duterte disallowed Americans from building facilities in the Bautista Airbase in Palawan, which faces the hotly disputed Spratlys chain of islands. Duterte has also refused to raise the Philippines’ landmark arbitration victory over China at ASEAN meetings.

While not opposed to the discussion of the South China Sea disputes in generic terms, Duterte prefers to instead focus on areas of presumed consensus within ASEAN such as counterterrorism and transnational crime, particularly the proliferation of illegal drugs. Duterte is particularly interested in using the ASEAN platform to promote and defend his controversial war on drugs at home, especially when he will deliver the annual chairman’s statement in November.

Many in the Philippine security establishment, however, want the South China Sea issue front and center in the ASEAN agenda this year. In contrast to Duterte, they want to use the Philippines’ victory in the arbitration case last year in The Hague, a victory based upon the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, as a basis for the formulation of a legally-binding COC in the South China Sea.

The Philippines’ recently-dismissed foreign secretary, Perfecto Yasay, who failed to garner confirmation from Philippine Congress due to his failure to disclose his American citizenship, suggested that he wanted to pursue this approach to the South China Sea during the ASEAN Foreign Ministers Meeting in Boracay, Philippines. Other members of the Philippines’ foreign policy establishment, such as Secretary of Defense Delfino Lorenzana, have consistently raised concerns about China’s creeping challenge to the Philippines’ territorial claims and sovereign rights in eastern (Benham Rise) as well as western (Scarborough Shoal) waters of the South China Sea.

The larger problem, however, is whether the ASEAN can achieve unanimity on sensitive issues, when certain members, particularly Cambodia, have stridently toed Chinese line on the South China Sea issue. In his annual press conference, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi made a surprising announcement that a first draft of a COC has already been finalized. Yet, neither he nor any ASEAN official has clarified its key elements or who will ensure compliance if a Code of Conduct is actually completed. And if ASEAN can make no headway on the most important regional security issue, the organization will look extremely weak, even while celebrating its fiftieth anniversary.

Online Store

Online Store