Just How Much Money Should the Border-Adjusted Tax Raise Be Expected To Raise?

I have a new paper out with David Kamin of New York University Law School—it will be formally out in Tax Notes in a couple of weeks, but given that there is a live debate on the topic, we are posting it in draft form now—and the New York Times had a related editorial linking to it earlier this week.

So this is a joint post with David Kamin.

More on:

Our paper makes two arguments.

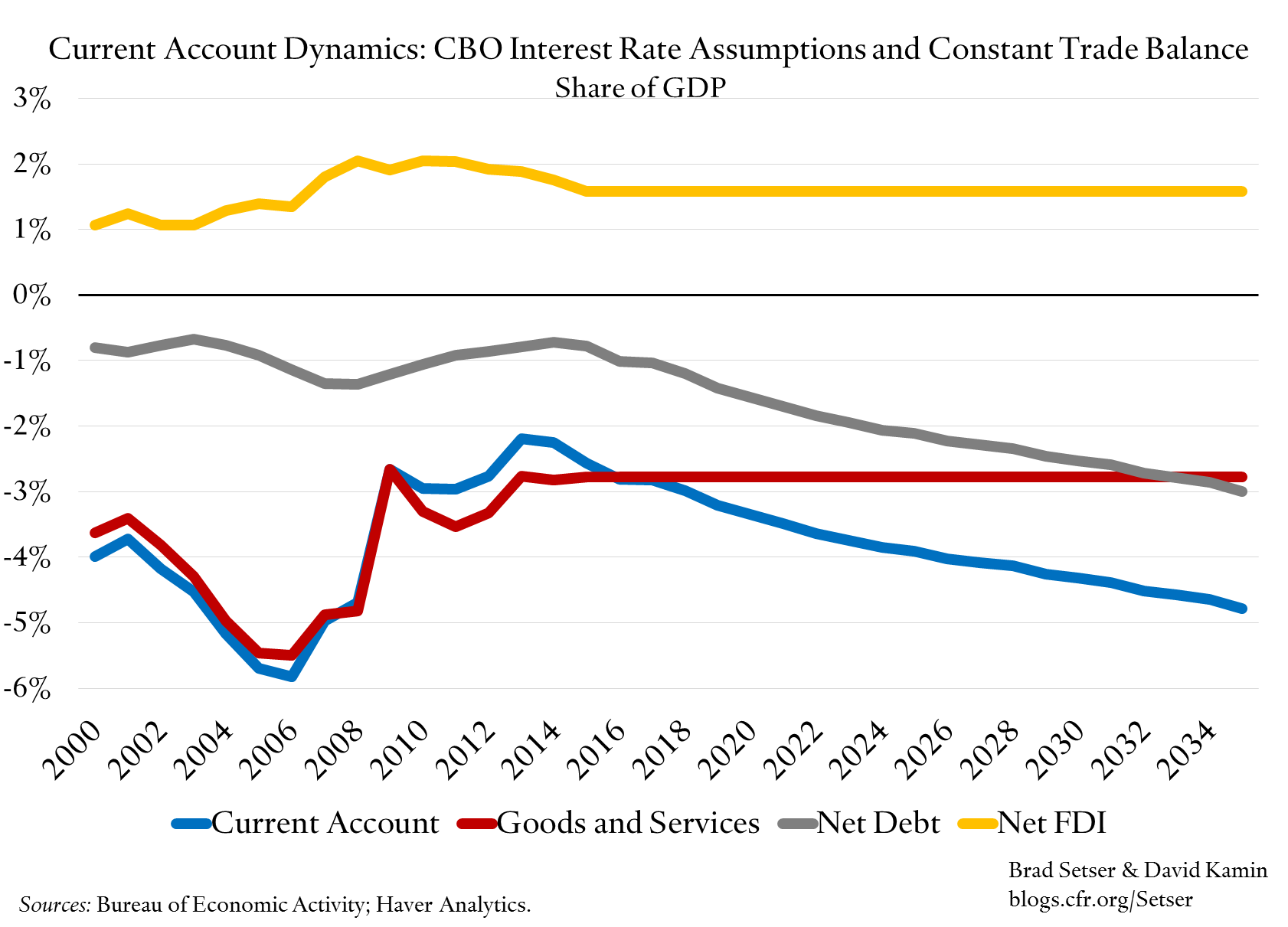

1) Even with fairly optimistic assumptions about long-term growth and long-term interest rates and the persistence of “excess returns” from U.S. direct investment abroad, the U.S. cannot sustain trade deficits of approaching 3 percent of GDP over the long-run. The CBO’s estimates for long-run growth and the long-run nominal interest rate on the U.S. debt stock imply a sustainable long-run trade deficit of about 1 percent of GDP. That would generate maybe 20 basis points of GDP in permanent revenue. If the excess returns (“dark matter”) on U.S. foreign direct investment go away, the U.S. would need to run a small trade surplus—and the border adjustment would lose revenue over the long-term.

As a result, realistic projections of revenue from a border adjustment should show that revenue falling considerably and, possibly, entirely disappearing over the long-term.

Remember the border adjustment acts as a tax on imports (imports are not deductible as a cost) and a subsidy for exports (a portion domestic wage and other content of exports is effectively rebated, as exports are not considered revenues while domestic wages are considered expenses, creating a tax loss). So it only generates revenue in net if the revenue collected on the border adjustment on imports exceeds the revenue lost on the export rebate.

More on:

This is actually standard old school IMF external debt sustainability analysis.* The basic logic is simple. Sustained trade deficits over time lead to a build-up of external debt, and it is impossible to borrow forever both to run trade deficits—as over time you have to borrow both to finance the trade deficit and the interest on your accumulated debt. Countries can run modest current account deficits over time without rising external debt, but they cannot run trade deficits over time (well, technically, the non-interest current account, not the trade deficit) without an ever-rising stock of external debt to GDP.

For those more familiar with fiscal sustainability, the trade deficit is roughly analogous to the primary fiscal balance. A modest headline fiscal deficit is often consistent with a stable debt to GDP ratio, but a large primary fiscal deficit generally is not.

An obvious irony: a border adjustment is the only source of the long-term revenue Paul Ryan needs to make the tax reform permanent through the budget reconciliation process if the U.S. is projected to run permanent trade deficits. Or in the terms of Trump’s campaign, if the U.S. keeps losing at trade—an overall deficit means lots of bilateral deficits.

2) The actual revenues that the border adjustment will generate will be a function of how transfer price and similar tax games evolve, not just how the trade balance evolves—and current estimates fail to take into account the fact that the border adjustment will be avoided to some significant degree. To be sure, it might very well reduce the considerable tax gaming that we see in the current system—but not by 100 percent.

Exempting exports from corporate income tax (and providing a rebate against domestic costs) while taxing imports removes the incentives for some tax games, but creates incentives for others. Especially if the U.S. alone adopts a destination-based cash flow tax.

The border adjustment would remove the incentive for some existing tax games. That is a attractive feature of the proposal. Some firms try to shift profits made in the U.S. outside the U.S. through creative transfer pricing—say importing drugs invented in the U.S. from Ireland for example, and booking the profit on U.S. sales in Ireland. A destination based tax would help there.

It also would end firms’ needs to game the U.S. system when it came to export of intellectual property—probably the largest distortion in the current system. Notably, though, it would do so by giving up U.S. taxes of the global export of U.S. intellectual property and possibly turning the United States into a tax shelter from other countries’ source-based tax systems. Right now, tech companies do not so much avoid tax on their U.S. profits as avoid tax on their global profits—Apple Ireland gets the rights to Apples IP for Europe, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa, and those profits are effectively untaxed (at least until the funds are repatriated back to the U.S). A destination-based cash flow tax would entirely exempt revenues from the exports of the intellectual property from tax, so it wouldn’t matter if the profit was booked in Ireland or California (and if Apple’s domestic cost exceeded its domestic revenues, it might even get a rebate). Only the destination would matter from the U.S. perspective.

We consequently would expect that exports of intellectual property would rise sharply with the tax reform, bringing down the reported trade deficit—in part because companies will try to avoid remaining source-based taxation of other countries. After all, if Germany still taxes based on source of the profit and the United States does not, it makes all the sense in the world to report that profit in the United States! However, this new gaming would almost entirely affect the revenue bases of other countries, not the revenue base of the United States.

But the incentive to export—and for businesses to avoid importing—would create new kinds of tax games that do affect the U.S. tax base and that revenue estimates we’ve seen don’t seem to take into account. Specifically, there would be—as David Hemel has noted—strong incentives to book U.S. sales as exports where possible. A firm would export to an offshore subsidiary and deduct its exports from revenues. And then sell directly from abroad to consumers, avoiding any business tax.

More generally, firms that import would try to sell directly to consumers if the tax was entirely collected through businesses. In order for it to work, you actually have to have “VAT” style border enforcement to avoid leakage.

Here is an example, one Brad got from his father, who brought back a German car as a souvenir while on sabbatical in the 1960s:

Go on a vacation in Europe. Pick up a BMW in Munich. Spend a couple of weeks touring. Put your new car on a ship—and fly back to the U.S. Then pick up your (almost) new car at the nearest port. You pay the shipping, but not the 20 percent border-adjustment. Not if the border adjustment is imposed through business tax filings.

Think that won’t happen? Think again. They way to stop it is to do actual adjustments for any goods at the border. But then it isn’t just a business income tax. And policing virtual borders is even harder.

Realistically some leakage is inevitable—and needs to be factored into the revenue estimates. Simply taking the current trade deficit and multiplying it by 20 percent (or whatever the new tax rate is)—what some current estimates do—is almost sure to over-estimate actual revenues.

And then there’s the fact that trade deficits should dissipate over the long-term.

* New school IMF debt sustainability analysis focuses almost entirely on fiscal debt sustainability. Brad thinks that is a step backwards.

Online Store

Online Store