Latin America’s Savings Problem

More on:

Savings are essential for growth: domestic savings finance productive investment, provide a safety net for the future, and are strongly associated with long-term growth prospects. Sadly, a new report from the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) makes the convincing case that Latin America has fallen behind, with repercussions for development in the region for decades to come.

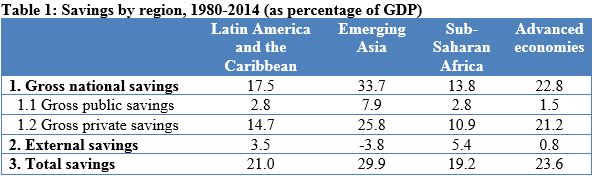

National savings result from the combination of decisions by individuals, businesses, and the public sector. On all of these fronts, Latin America does relatively poorly, as shown in Table 1: gross public savings are only a bit more than one-third those of emergent Asian economies, while private savings are 69 percent those of advanced economies and only 57 percent of emergent Asian economies.

Latin America’s only saving grace (pun intended) is that external savings partly compensate for low national savings. But foreign savings such as foreign debt are less desirable than domestic savings, not least because they may be comparatively expensive and may also make national economies more susceptible to foreign shocks.

Who is to blame for low savings? The report notes that Latin America and the Caribbean did poorly at saving during the region’s demographic boom, with the result that average savings are about 8 percent lower than where they could have been. Low levels of trust in the financial sector contribute: only 16 percent of the region’s adults have savings accounts, against 40 percent in emerging Asia and 50 percent in the advanced economies. Banks in Latin America only loan around 30 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) to the private sector, as compared with 80 percent in Asia and 100 percent in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). In the absence of good financial sector options, citizens and businesses may turn to options that are less desirable for long-term development, like sending money abroad, purchasing durables, or simply consuming instead of investing. Also problematic is the rapid aging of Latin America, which will put pressure on pension systems, many of which do not yet cover even half of the national population.

Government consumption is also a significant part of the problem, in part because the region so desperately needs to increase investment in long-term infrastructure projects that governments may be better positioned to provide. The IADB estimates regional economies need to increase such investment by 1 to 2 percent a year. But for a variety of reasons, governments have found it easier to bias spending toward consumption: between 2007 and 2014, total government spending increased by 3.7 percent of GDP, but the report notes that 90 percent of this increase went to current expenditure, and public investment accounted for only 8 percent. The report minces no words when it comes to the problems of tax arrangements: tax evasion accounts for more than half of potential tax revenue in the region, which places much of the burden on compliant citizens, who then have every incentive against saving, with pernicious effects on aggregate investment and productivity.

What can be done? The answer, according to authors Eduardo Cavallo and Tomás Serebrisky, lies in a combination of pension reform, infrastructure investment, more targeted tax policies, efforts to build productivity, and financial sector reform. As though this were not a daunting enough list, they also suggest that Latin America needs to create incentives for a “savings culture,” including by improving access to the financial system, developing new and more accessible savings products, and adopting microeconomic policy to provide better incentives. It is a daunting agenda, and at times seems to include everything but the proverbial kitchen sink (in this case, the kitchen sink would be a greater discussion of the role of political institutions that get in the way of building the proper regulatory environment, institutional trust, and compliance).

Overall, the report provides policymakers with a useful framework for thinking about the conditions for Latin American development over the long haul, and a reminder that Latin American leaders must pay far more attention to strategically selecting long-term economic policies, particularly as the demographic boom eases away and the turn-of-the-century boom times recede into memory.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store