More on:

Sungtae “Jacky” Park is research associate for Korea studies at the Council on Foreign Relations and is the author of The Korean Pivot and the Return of Great Power Politics in Northeast Asia.

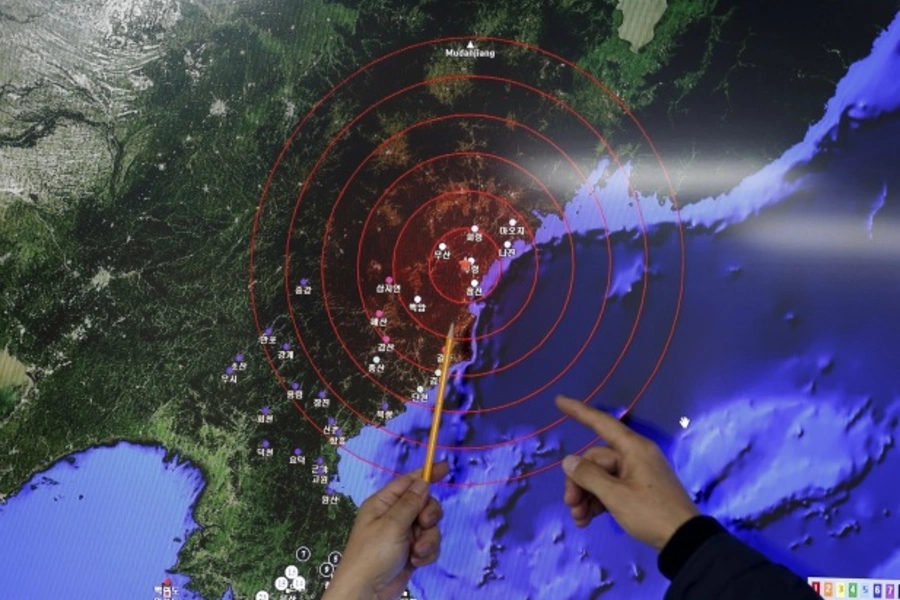

Over the past couple of days, news headlines have been exploding with contents about North Korea’s claims to have tested a hydrogen bomb. Based on the 5.1 magnitude of the earthquake caused by the test and other related indicators, most experts are skeptical that the test was of a hydrogen device, suggesting the possibility that the test could have been of a “boosted weapon” that uses a small level of fusion to enhance a fission bomb. Yet, the media gave far less attention to North Korea’s December 21 submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) ejection test, which might have succeeded or failed, depending on sources. The different levels of publicity that the North Koreans gave to the two tests perhaps hint at Pyongyang’s intentions.

While a hydrogen (fusion-based) bomb is indeed approximately one thousand times more powerful than the fission-based bomb dropped on Hiroshima and would help with efforts to miniaturize a deliverable warhead, it is unlikely that the North Koreans actually tested a hydrogen device. Moreover, whether a warhead consists of a hydrogen bomb or otherwise, the deterrent effect of a nuclear weapon would remain the same. Any nuclear attack on a populated area would be devastating. Hence, the strength of nuclear weapons does not matter so much when it comes to deterrence calculations.

Given that North Korea already tested nuclear devices three times before, the likely purpose of Pyongyang’s recent announcement of a supposed hydrogen bomb test was primarily political. Although the device was not a true hydrogen bomb, there was an earthquake, newspapers and TV stations perked up their ears at the word “hydrogen,” and people around the world immediately had a giant mushroom cloud in their imaginations. The events in the Middle East and Europe had drawn the world’s attention away from North Korea for some time. With a half-baked “hydrogen” bomb test, the Kim Jong-un regime succeeded in refocusing the entire world’s attention on North Korea again. In this respect, Kim, much like his father, seems to have the knack for effective public relations.

Why North Korea seeks attention is anyone’s guess, but Pyongyang likely seeks to draw Washington into talks for the unattainable purpose of getting the United States to recognize North Korea as a legitimate nuclear weapons state. Furthermore, Pyongyang is likely using the nuclear test as a way to boost the Kim regime’s legitimacy at home. An added benefit would be that North Korea has made a technological advancement toward building a more powerful nuclear device, if not a hydrogen bomb.

Nevertheless, the SLBM ejection test in December, while not covered as much as the nuclear test by the media, should be considered a more serious concern. The purpose of the SLBM test, whether it succeeded or not, was clearly to develop a more secure nuclear deterrent that could eventually reach the United States. Compared to the relative strength of a nuclear device, diversification of delivery vehicles is a development that has strategic implications for the United States and its allies by making the task of tracking and destroying the launching devices more difficult in a hypothetical military conflict.

In responding to North Korea, the policy priority should be on measures designed to halt Pyongyang’s missile development rather than focusing on what type of bomb the Kim regime has in its arsenal. North Korea has been steadily working on extending the range of its missiles as well as diversifying the means of delivery. By the time Pyongyang’s efforts bear fruition and make the headlines, it may well be too late.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store