TWE Remembers: Woodrow Wilson Asks Congress to Declare War on Germany

Presidents win elections by making promises to voters. But keeping those promises can prove impossible to do. Just ask Woodrow Wilson. He won reelection in November 1916 on a pledge to keep the United States out of World War I. Five months later he was asking Congress to declare war on Germany.

Foreign policy, let alone war, was far from Wilson’s mind when he first won election in 1912.He defeated incumbent Republican President William Howard Taft and third-party candidate Theodore Roosevelt with his promise of a New Freedom, an ambitious call to expand the federal government’s role in promoting economic competition and protecting worker rights. He spent much of his first term making good on his promise, persuading Congress to pass legislation instituting a graduated federal income tax, establishing the Federal Reserve and the Federal Trade Commission, and prohibiting child labor. But Wilson always suspected that events might redirect his focus away from domestic affairs. He told an old colleague shortly before being sworn in on March 4, 1913, “It would be the irony of fate if my administration had to deal chiefly with foreign problems.”

More on:

The war that came to Europe in August 1914 did not interest most Americans. Since the days of Washington’s Farewell Address, Americans had resisted the temptation to become involved in what Thomas Jefferson called “entangling alliances” with Europe. So it was hardly surprising that Wilson’s immediate reaction to the “Guns of August” was to declare the United States “neutral” in Europe’s war. He even went so far as to urge Americans to remain “impartial in thought as well as in action.”

Wilson discovered, however, that neutrality was easier to preach than to maintain. Part of the problem was the nature of American trade. It favored Great Britain and the Allied Powers before the war began, and with Britain’s dominance of the high seas, that tilt only increased with time. By 1916, U.S. trade with the Allies had ballooned to $3.2 billion; trade with Germany and the Central Powers meanwhile shriveled to a mere $1 million. Wilson considered the United States neutral, but to German officials the Americans looked like a British ally.

Berlin, not surprisingly, refused to let support to its mortal enemy go unchallenged. German submarines sank neutral shipping where they could, sometimes with a stunning loss of life. On May 7, 1915, a German U-Boat sank the Lusitania, a British luxury liner, killing 1,198 people, including 128 Americans. Most Americans denounced the attack as barbaric and uncivilized. They were not moved by German claims that the Lusitania was being used to ferry guns and ammunition to Great Britain. Under pressure from Washington, Berlin eventually halted the submarine attacks, at least for a time.

Making matters worse for Wilson was that the fighting in Europe wasn’t just a foreign policy problem. It was also a domestic political problem. In 1914, one out of seven U.S. residents was foreign born, and many more were second- or third-generation immigrants. Sympathies (and antagonisms) toward the war’s protagonists frequently followed ancestral ties. German immigrants and their children favored the Kaiser, or at least opposed calls for the United States to side with Britain. Most Irish Americans, bitter over Britain’s refusal to grant Ireland its independence, felt the same way. Wilson recognized the political dangers of antagonizing both constituencies, arguing that neutrality was necessary because “otherwise our mixed populations would wage war on each other.”

Some leading Americans pushed Wilson to be scrupulously neutral. One such person was the man who engineered Wilson’s nomination in 1912 and who subsequently became his secretary of state, William Jennings Bryan. Perhaps the most beloved member of the Democratic Party—he was its presidential nominee in 1896, 1900, and 1908—Bryan believed that true neutrality required banning American citizens from traveling to war zones. When Wilson sent Germany a formal protest over the sinking of the Lusitania but failed to protest British violations of neutral rights, Bryan resigned as secretary of state.

More on:

Other prominent Americans dismissed neutrality as the policy of the feckless. The leading voice on this score was Theodore Roosevelt, who derided Wilson’s “cult of cowardice.” TR had his fans in the press. The day after the sinking of the Lusitania, the New York Herald ran a headline exclaiming, “WHAT A PITY THEODORE ROOSEVELT IS NOT PRESIDENT!”

Despite calls from Roosevelt and others for war, Wilson ran for re-election in 1916 on a peace platform. His slogan was simple: “He Kept Us Out of War.” The message worked. Wilson won a close election over Charles Evans Hughes. (Hughes is the only Supreme Court justice to resign from the nation’s highest court to run for president. He failed to reach the White House, but he did become secretary of state under Warren Harding, and Herbert Hoover appointed him chief justice of the Supreme Court.)

Much changed, however, between the November 1916 election and Wilson’s swearing in for a second term on March 4, 1917. On January 31, 1917, Germany decided to resume unrestricted submarine warfare against U.S. ships. A month later, Wilson learned of the Zimmerman Telegram, Germany’s offer to help Mexico reclaim the territories it had lost to the United States seven decades earlier. In mid-March, German U-boats sank three U.S. ships in a matter of days.

Wilson reluctantly concluded that war could not be avoided. He agonized over his decision; he worried what war would do to the country.

To fight you must be brutal and ruthless, and the spirit of ruthless brutality will enter into the very fiber of our national life, infecting Congress, the courts, the policeman on the beat, the man in the street.

But as he told a close confidant, “What else could I do?”

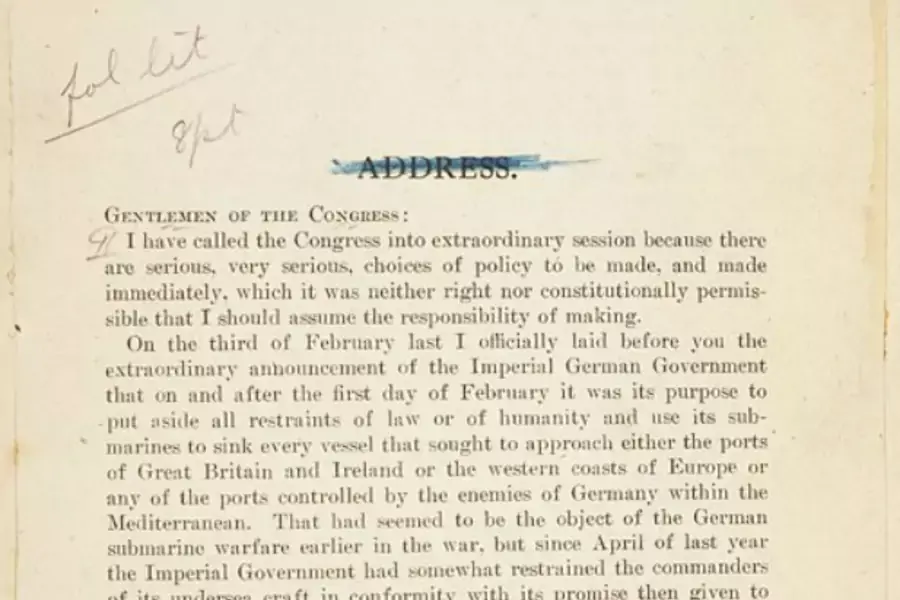

At 8:30 PM on April 2, Wilson went before a joint session of Congress and requested a declaration of war against Germany. He insisted that the “German submarine warfare against commerce is a warfare against mankind.” But Wilson wasn’t content to root his call for war in self-interest or self-defense alone, however justified. The son of a righteous Presbyterian minister had a far nobler motive in mind. Using words that would long outlive his speech, he declared:

The world must be made safe for democracy. Its peace must be planted upon the tested foundations of political liberty. We have no selfish ends to serve. We desire no conquest, no dominion. We seek no indemnities for ourselves, no material compensation for the sacrifices we shall freely make. We are but one of the champions of the rights of mankind.

On April 4, the Senate voted 82 to 6 for for war. The House of Representatives followed suit on April 6 by a margin of 373 to 50. American doughboys would not see combat in Europe for another six months. But a campaign promise had already fallen by the wayside.

Online Store

Online Store