Using Data to Uncover Hurdles for Mexico’s Female Diplomats

More on:

Voices from the Field features contributions from scholars and practitioners highlighting new research, thinking, and approaches to development challenges. This article is authored by Tania Del Rio, Cultural Bridge Fellow with the Harvard Kennedy School’s Women and Public Policy Program.

Every January, 157 notable guests arrive in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, or SRE) in Mexico City. Many of them share valuable skills and qualities. They are knowledgeable about Mexico’s economy, its politics, and its people, and they are deeply invested in the country’s progress. They will meet with key figures in government, civil society, business, and academia over the course of a week. They are Mexico’s Ambassadors and Consuls, who represent and assist Mexicans all over the world. But they share one additional trait that often goes unmentioned: 75 percent of them are men.

In 2006, the Committee for the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women of the UN Convention on the Elimination and Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), recommended that Mexico “accelerate efforts to promote women to positions of leadership, including in the Foreign Service,” after noting with concern the small number of women in decision-making positions in those areas. Since then, the Ministry has made efforts to address this issue with some notable results. This January, during the 27th Meeting of Ambassadors and Consuls, Minister Claudia Ruiz-Massieu announced that the next batch of ambassadorial appointments would be 50 percent female. This is an encouraging first step, but much remains to be done.

As a Cultural Bridge Fellow with the Harvard Kennedy School’s Women and Public Policy Program, I worked closely with the ministry in recent months, using data to identify the reasons why there are so few women in the top echelons of Mexican diplomacy. I built a dataset that tracks active Foreign Service Officers throughout their careers to see what stages present increased risk of career stagnation for women. What I found was surprising.

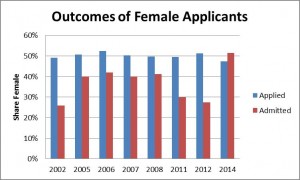

It turns out that, despite efforts to create an open and fair process for selecting officers to become Mexico’s next diplomats, the entrance examination is a significantly more difficult hurdle to clear for women than for men. Since 2002, when the examination in its current form first came into use, 7,982 people have applied to become Foreign Service Officers. Of those, 4,096 (51.3 percent) were women. A total of 277 were selected to enter the Foreign Service in that time span; of those, only 101 were women (36.4 percent). For every year except 2014, a much higher proportion of women applied than was admitted.

This is puzzling, as the exam is supposedly an unbiased evaluation of skill. It consists of three multiple choice tests on general culture, Spanish and English language, and a third language, as well as two interviews, a written essay, and a psychological examination. The drop off for women came in the general culture and Spanish multiple choice tests.

|

|

There may be several possible explanations for this. We could hypothesize that the Mexican school system is not preparing men and women equally academically, or that the SRE is attracting a set of female candidates that is not sufficiently prepared for the test, or that men and women are equally prepared, but that the test is inherently biased in some way. The next step for the SRE is to test each of these hypotheses and parse out whether the best way to tackle the problem is through better recruiting, revising test questions and interview formats, or helping train potential test takers.

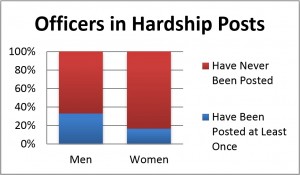

Uneven performance in entrance examinations explains a large part of the gender gap among diplomats, but not all of it. Women in the Foreign Service are promoted less than their male peers, especially if the share of women among officers with the same seniority level is higher than 30 percent. Promotions are awarded through exams similar to those in the entrance process, combined with self and supervisor evaluations. Additional points are awarded for high responsibility posts and posts in places where officers are likely to endure additional hardship, such as war-torn regions, or locations where there is limited access to basic necessities or high rates of crime.

The data on the promotion exam results show that men and women perform equally well in the exams, but that women are 45 percent less likely than men to ever be posted to places of hardship, which award an extra point in the evaluation process. Women are more likely to be assigned to lower responsibility posts, amounting on average to .18 points less in their overall exam scores. In an exam where the difference between promotion and career stagnation can result from variances in hundredths of points, this seemingly small variance in fact matters greatly.

|

The Ministry should reevaluate the way it allocates officers to posts of different responsibility levels to ensure that women are not disproportionately assigned to less challenging work—the current allocation may reflect deep-seated gender bias about women’s abilities to be successful in hardship posts. In the same vein, the Ministry should actively recruit more women to occupy hardship posts, while taking the necessary steps to guarantee the safety of all officers stationed to difficult places.

More broadly, using data to diagnose the sources of a problem like gender underrepresentation in decision-making roles is a highly effective way to create solution-oriented interventions. It can help an institution identify the most critical pressure points to attack the issue. And data is vital in benchmarking the performance of new policies and measuring progress. With this dataset in place, for example, the Mexican Ministry of Foreign Affairs can evaluate the effect of policies it implements moving forward, and concentrate on further developing the most effective ones. Through this effort, the Ministry will continue to demonstrate that Mexico is fully committed to promoting gender equality—not only in rhetoric, but in action.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store