Why Did China’s 2016 Current Account Surplus Fall?

More on:

Few policies are less liked than China’s 2015/2016 credit-driven stimulus. Even people like me who worried that slamming the brakes on credit, in the absence of more fundamental reforms to lower China’s savings rate, risked creating a shortfall in demand were not exactly enthusiastic supporters. China would be far better off if had used a rise in central government social expenditure to support demand, not yet another wave of off-balance sheet borrowing by local governments and state firms.

But the current pick-up in growth suggests that arguments that (yet another) expansion of credit wouldn’t work were a bit overdone. There are no doubt better ways to support growth than more credit. But growth did responded to the stimulus, even if there is a real debate over just how strong the response was.*

Tilton, Song, Tang, Li, and Wei of Goldman Sachs (in a report summarized here):

"Chinese policy makers wrestled with challenges throughout 2016, but large and sustained policy stimulus eventually fostered recovery. ... Our China Current Activity indicator bottomed out at 4.3% in early 2015, recovered to the mid-5 percent range last year, and is now running at 6.9%. Heavy industry ... has seen an even more pronounced re-acceleration"

And there is growing evidence, I think, that the pickup in Chinese demand also had positive spillovers for the rest of the world.

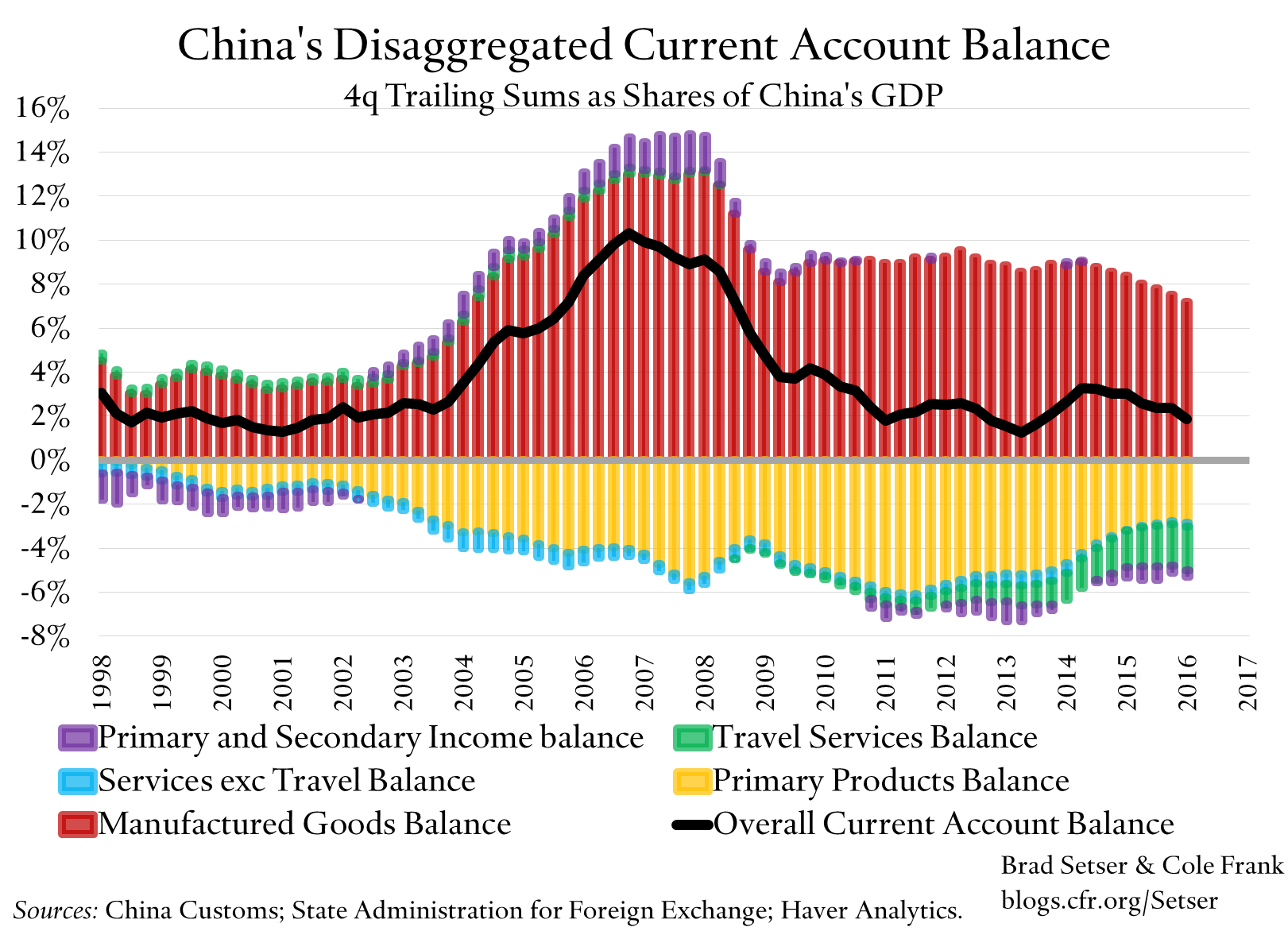

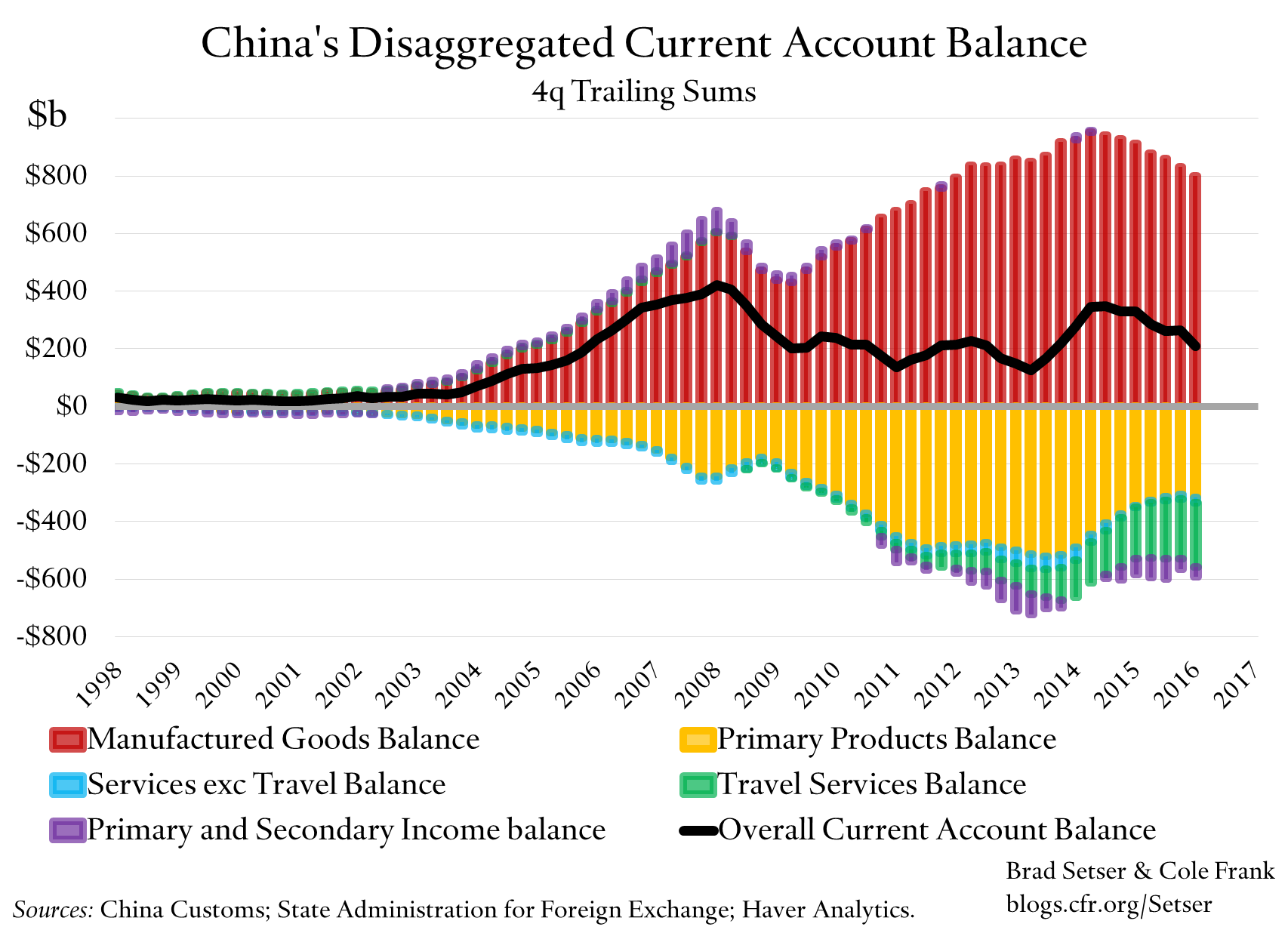

China’s current account surplus for 2016 fell more than I expected. To be sure, China’s reported current account is prone to significant revisions, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the (very low) q4 surplus is revised up.

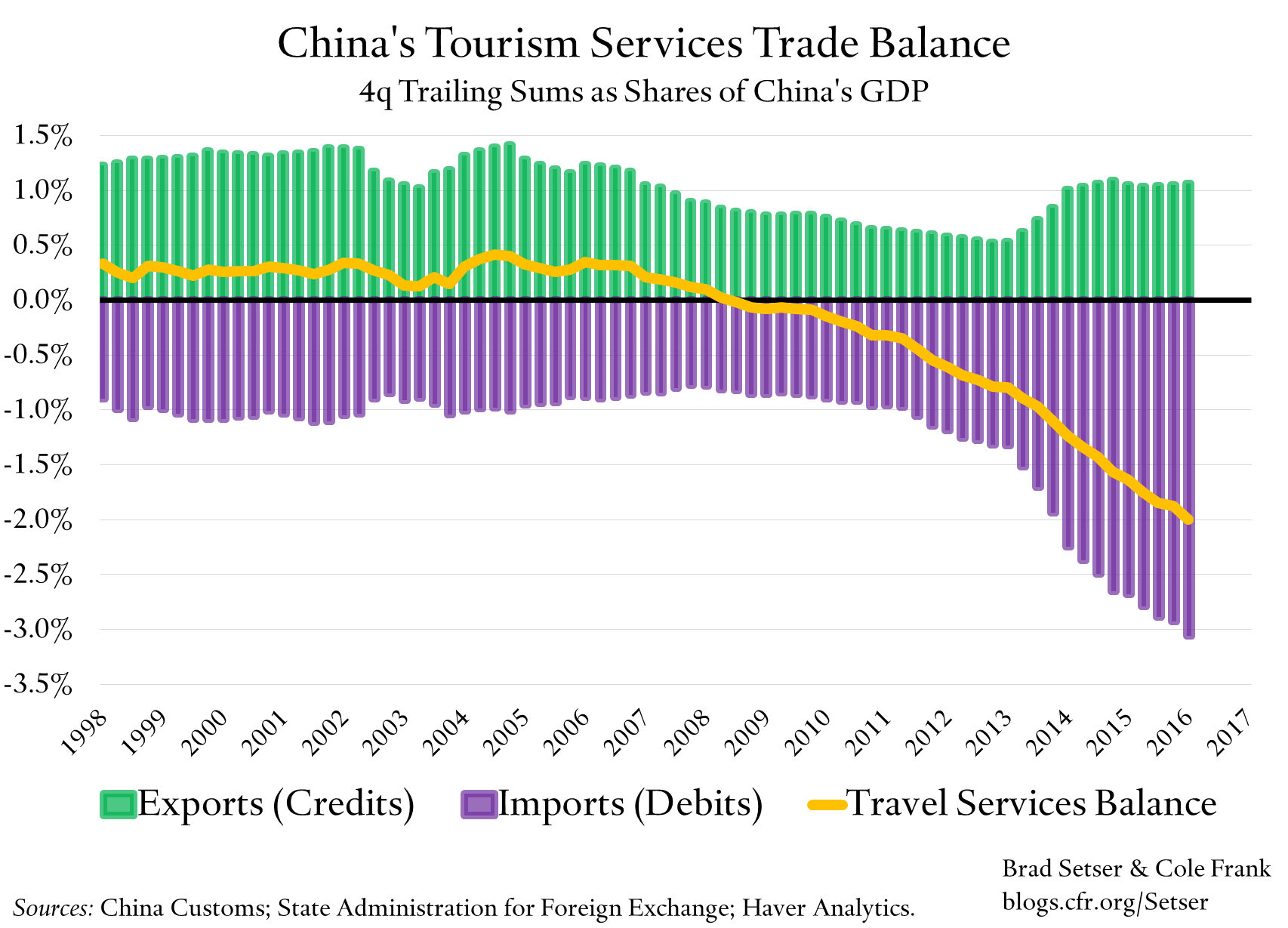

I also do not take China’s reported data as gospel. For example, I am skeptical of the run up in China’s tourism imports—reported imports have almost tripled, going from $130 billion in 2013 (1.3 percent of GDP) to $340 billion in 2016 (around 3 percent of GDP). That kind of growth is hard to explain—it is far faster than the growth that could be explained by the ongoing rise in the number of China’s tourists, even accounting for higher per tourist spending. The revised data collection methodology that led to the “surge” in tourism imports is clearly capturing something new. As a result, I think China’s true current account surplus is a bit bigger than reported in the official data.

But the rise in the tourism deficit in 2016 only explains $40 billion of the $120 billion change in China’s current account surplus. Much of the rest comes from a fall in China’s surplus in manufacturing. And that is—best i can tell—"real." It is echoed in the fall in the U.S. trade deficit with China.

Do not get me wrong. China’s surplus in manufacturing remains huge. Too big for the global economy. Best I can tell, China’s trade surplus in manufactures, as a share of China’s GDP. exceeds total U.S. exports in manufacturing, as a share of U.S. GDP. That says something both about China and about the U.S.**

But directionally China’s surplus came down. The fall incidentally shows up in the U.S. data as well—U.S. imports from China fell in 2016 in dollar terms, and I think in real terms too.

Partially that is because exports remained fairly weak. The acceleration in export volume growth in q2 wasn’t sustained in q3 and q4. Q4 in particular was weak (the price data indicates that December export volumes fell—though this may be a statistical artifice, as January now looks to be exceptionally strong)

And import volumes picked up. They are still growing more slowly than the economy—so China is still “deglobalizing” in a fundamental sense (imports are falling as a share of GDP). But 4 percent year-over-year growth is better than no growth.

The revival of China’s import demand has contributed to the recent rebound in Asian and global trade. And China’s stimulus also helped support a rebound in global commodity prices, taking pressure off some vulnerable emerging economies.

The means that China used to stimulate its economy in 2016 remain dubious. China would be better off with more fiscal spending and less crazy lending. It desperately needs a fundamental expansion of its system of social insurance. At the same time, the global economy would be weaker right now if China hadn’t turned open the taps and allowed domestic credit to flow in late 2015 and early 2016.

* The acceleration in growth does not show up in the official growth data, which makes analysis of the growth impulse from the stimulus difficult (to say the least). But like many I do not trust the headline GDP numbers. Nominal growth picked up, as did a host of other indicators that should correlate with activity, like import volumes. I strongly believe that growth fell by more than reported in 2015, and that the rebound in the "physical" indicators of Chinese growth in 2016 reflects a real acceleration. But I also realize that is an impossible to falsify hypothesis.

** China’s manufacturing surplus is just over 7% of China’s GDP. U.S. exports of manufactures can be measured different ways -- but are now a bit over 5% of U.S. GDP. Table 15 of the trade release puts total manufacturing exports in 2016 at $1051 billion, or 5.6% of U.S. GDP. In dollar terms it is closer than it should be.

---

Charts in billions of USD:

More on:

Online Store

Online Store