Don’t ignore the adjustment that has taken place; the US trade deficit is half its size this time last year …

More on:

Most reporting on the May trade data tried to fit it into the “green shoots” meta-narrative, thanks to the small uptick in exports. Never mind that total exports were about equal to their level in March even after the May uptick– and that about half the uptick between May and April came from a sharp rise in petroleum exports (see Exhibit 9). I have a hard time seeing how that signals a sustained uptick in US activity.

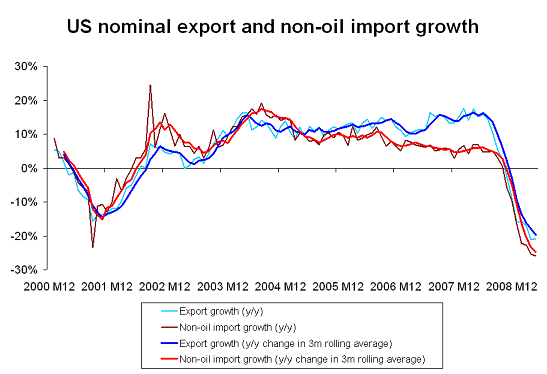

On a y/y basis, the fall in exports does seem to have stabilized. Moreover, the y/y fall in exports seems to have stabilized with a bit before the fall in imports stabilized, and the percentage fall in non-oil imports (around 25% y/y) is a bit larger than the percentage fall in non-oil exports (around 20% y/y).

But y/y changes don’t tell us all that much. Levels are what count.

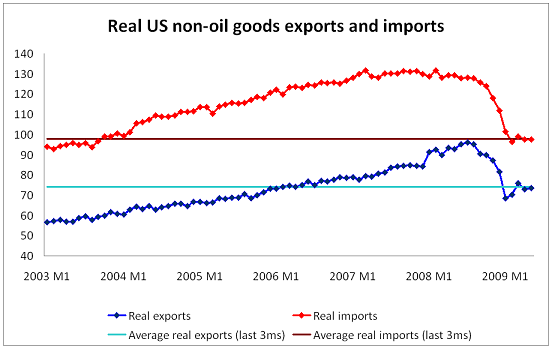

Real (goods) exports and especially imports have been essentially flat for the last three months or so. The Los Angeles and Long Beach port data suggests nothing much changed in June. That is progress. Exports, imports and indeed activity were all in free fall for a while in q4 and q1. But the trade data – backward looking data, to be sure – still fits comfortably with Jan Hatzius’ argument that final demand is going sidewise more than recovering.

But exports have stabilized after a smaller fall than imports. Real exports are at their late 2005 levels. Real imports are at their late 2003 levels. That means the non-oil trade deficit has fallen significantly.

The non-oil deficit over the last three months was only $40 billion -- about 1/3 of its level in late 2005 and early 2006. The non-oil deficit actually isn’t that far from the levels typical of most of the pre-boom 1990s.

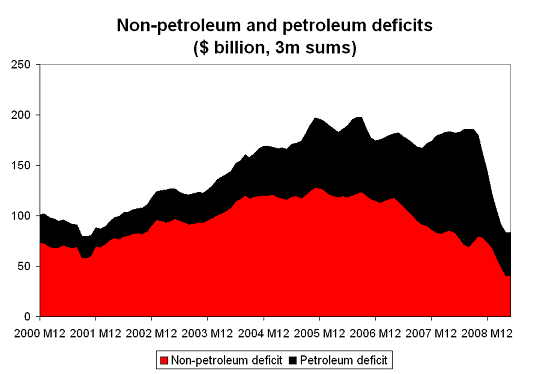

Of course, oil prices aren’t likely – unless you believe Philip Verleger – to return to their 1990s (or 2002) levels, so the overall deficit is still a bit bigger than it was in most of the 1990s.

Still, there has been a major adjustment. The question is whether it will be sustained when the US recovers and US demand picks up.

That depends on the course of the dollar, to be sure. And of the course of the dollar depends on whether private demand for US assets picks up, as well as whether countries like China maintain dollar pegs. But it also depends on the nature of the global recovery – and the strength of stimulus policies other countries adopt. And their at least there is a bit of hope, at least so long as China sustains its current highly stimulative policies. China’s June surplus was lower than expected, in part because China’s imports picked up before China’s exports. That’s goods news for global adjustment.

There sometimes is a tendency to speak about the world’s macroeconomic imbalances as if nothing has changed. That increasingly strikes me as a mistake. The world’s imbalances haven’t gone away, but they have shrunk dramatically.

Japan is now running an external deficit. China’s surplus shrank, at least in q2. The US deficit is much smaller now than in the past. Europe’s internal imbalances also have shrunk.

The adjustment came the painful way – with sharp falls in exports and imports. But it was still adjustment. The trade deficit fell sharply. The rise in the public borrowing buffered an enormous fall in private borrowing, and private demand. It cushioned rather than stopped the adjustment. The challenge now is try to make sure the recovery doesn’t undo the adjustments that happened during the crisis.

One last point: the lion’s share of the US deficit now comes from the United States petroleum import bill. Discussions about the policies that gave rise to imbalances typically focus on macroeconomic policy choices. That increasingly strikes me as incomplete. Energy policy should enter the calculus too. The US isn’t going to start exporting petrol – not on a net basis -- anytime soon. But it certainly could do more to reduce its demand for imported energy.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store