The IMF Needs to Focus on Setting Good Targets for External Debt Sustainability

There is no easy solution to the difficulties created by the reality that the Export-Import Bank of China (“Exim,” a policy bank and an official lender in China’s taxonomy) and the China Development Bank (CDB, also a policy bank, but a private lender in China’s taxonomy) are typically among the biggest creditors of a distressed frontier market that has been unable to pay its debts.

The IMF can spend time trying to rearrange the place settings around the negotiating table, but so long as the policy banks need state council approval to do anything other than extend their repayment schedule for more than a few years, China is going to be a difficult actor. The IMF cannot force the policy banks to take losses – the most it can do is adjust its internal processes (notably its policy on financing assurances) to make it more difficult for Exim (or another Chinese official lender) to block IMF crisis lending.

More on:

At least for now, the IMF can set the targets that define the amount of debt relief a distressed frontier market needs to seek from all its creditors. More specifically, all the creditors inside the scope of its restructuring – the multilateral development banks (MDBs) are often excluded, and in Sri Lanka central bank swap lines have been as well.

But I am not convinced that the IMF has been doing this job especially well. It certainly hasn’t been setting targets that are consistent across cases – and it doesn’t seem that the different targets relate in any reasonable way to differences in fundamental capacity to repay.

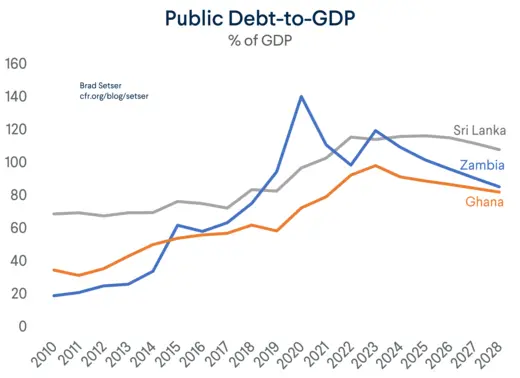

Sri Lanka, Ghana, and Zambia have some important similarities beyond all being in default.

For example, all have (or have had) overall public debt (both local market and external) of over 100 percent of GDP.

All have significant (over 40 percent of GDP, and in some cases 50 to 60 percent of GDP) external public and publicly guaranteed debt. External debt is important because it is a direct claim on scarce foreign exchange reserves, but it also tends to define the scope in the restructuring of a country’s hard currency debts.*

More on:

All three are also relatively poor, even if Sri Lanka’s per capita GDP puts it a bit over the cutoff for low-income countries. These countries aren’t at the same level of development as Argentina, Brazil, Egypt, or Turkey. If low-income implies low (external) payment capacity, all should have relatively low payment capacity.

But the restructuring targets set by the IMF differ wildly across the country cases.

Sri Lanka needs to get its public debt-to-GDP down to around 110 percent of its forecast GDP by the end of its IMF program in 2027.

Ghana’s public debt cannot be higher than 55 percent of its GDP at the end of its program period, and its external public debt is capped at 40 percent of its 2028 GDP.

However, the IMF has indicated that Zambia’s debt will remain sustainable with external public debt that will approach 50 percent of its GDP in 2028 if Zambia’s debt-carrying capacity is upgraded … drum roll … to match that of Ghana.

The IMF doesn’t explicitly set out the path of Sri Lanka’s external public and publicly guaranteed debt-to-GDP. In its wisdom, the IMF has concluded that only public debt-to-GDP matters for market access countries (Sri Lanka has graduated from being a “low-income country”), so there is no explicit analysis of Sri Lanka’s external debt levels at the end of its IMF program.

I repeat: there is literally no assessment of Sri Lanka’s external debt in the IMF’s debt sustainability analysis – and the IMF considers this a feature, not a bug.

In fact, forecasting the path of either foreign currency debt or external debt over the course of Sri Lanka’s program requires making a few assumptions, as the IMF doesn’t explicitly model the evolution of Sri Lanka’s foreign currency debt. But it seems that Sri Lanka will receive $5 billion in new fiscal financing from the MDBs during the program period. There is also a possibility that a significant share of Sri Lanka’s past-due interest will be honored, and additional interest will likely be capitalized between 2025 and 2027. Therefore, Sri Lanka’s $40 billion in external foreign currency debt seems set to rise to about $50 billion in 2027. Depending on the evolution of Sri Lanka’s dollar GDP (a point of dispute with Sri Lanka’s bondholder committee), that would put external debt between 50 and 60 percent of GDP. That is quite a high number for a country that is forecast to be returning to market borrowing in 2027 and that can make significant amortization payments from 2028 on.

Alternatively, consider external debt service relative to revenue. This is actually a slightly strange metric – debt service includes principal, and principal is usually refinanced rather than paid out of current revenue. But it is one of the measures used in the IMF’s low-income country (LIC) debt sustainability framework.

Zambia’s external debt service is limited to 14 percent of 2027 revenue in the base case (3.1 percent of GDP), or 18 percent in the upgraded debt-carrying capacity scenario (4 percent of GDP).

Sri Lanka’s external debt service isn’t specified, as the IMF doesn’t use “external debt” as a concept in its debt analysis for market access countries. But the 4.5 percent of GDP foreign currency financing need constraint functionally limits external debt service, and it works out to be 30 percent of 2027 revenue.

Ghana’s external debt service is limited to 18 percent of 2027 revenue, or 3.4 percent GDP.

Remember, Sri Lanka’s Achilles heel is that it is a low-revenue country. Pre-crisis revenues were (gulp) under 10 percent of GDP. It also has a relatively limited export base of around $16 billion, or 20 percent of current GDP – well below Ghana or Zambia. So, a constraint on external debt relative to exports (even at 140 percent of exports) would be rather tight.

To summarize, Sri Lanka – as assessed under the IMF’s market access framework – was judged able to support significantly more debt (versus GDP) than Ghana or Zambia, despite having a smaller revenue base. It was also judged by the IMF’s model as capable of supporting significantly more external debt (versus GDP) than Zambia or Ghana, even though it is has a significantly smaller export base.

Why? Well, the IMF’s market access model only looks at public debt. It doesn’t look at any measure of public debt-to-revenue.

The variables that matter for medium-term sustainability are, well, the size of the gross financing need and (I kid you not) the shape and width of the “fan” – that is, the fan chart of debt-to-GDP.**

Sri Lanka was judged capable of supporting debt-to-GDP levels of above 100 percent even though it got into trouble with debt-to-GDP of around 70 percent because its gross financing need is projected to be much smaller, and IMF’s model thinks fiscal risk correlates with gross financing need, not the stock of public debt.

And somehow, Sri Lanka’s large domestic banking sector makes it able to support a higher level of both external and domestic debt.

Plus, countries that already have experienced a big depreciation aren’t at risk of a further big depreciation, so in the IMF’s model, debt-to-GDP generally trends down.

Bottom line – across a host of metrics, Sri Lanka is judged able to support about twice as much debt as Ghana because it was assessed according to the market access country debt sustainability model.

And for what it’s worth, Ghana has actually had a lot of more recent “market access” than Sri Lanka.

Clearly, I believe that the IMF’s targets for Sri Lanka are off, and that they leave Sri Lanka exposed to a high risk of a future debt crisis. The notion that Sri Lanka can safely raise $1.5 billion a year in the bond market from 2027 with public debt-to-GDP of over 100 percent and external public debt of over 50 percent is quite simply a recipe for future default – and for “new” bonds that trade badly after the restructuring.***

The IMF, by contrast, believes that the low-income country model is outdated, as the thresholds for external debt sustainability aren’t empirically derived. The IMF also appears to believe that the focus on external debt is outdated in a world where local banks hold Eurobonds (though that is actually rare in Africa and other low-income countries) and foreign investors hold local law and local currency bonds.

But before the IMF’s shareholders sign off on a revision to the joint IMF-World Bank low-income country debt sustainability framework, they should understand why the market access country debt sustainability framework is, well, leaving countries with a lot more debt at the end of a debt restructuring than would be the case if countries were assessed using the the low-income country framework.****

Fundamentally, the IMF’s management and shareholders need to decide if 60 percent external debt-to-GDP – or for that matter, 50 percent – is too much for low-income countries, or for countries that have just crossed the threshold to become “market access” countries.

Because the apparent result of the initial application IMF’s bright, shiny, new debt model for market access countries is debt targets which imply that significantly higher levels of debt are sustainable.*****

* In a crisis, local law foreign currency-denominated debt tends to be settled in local currency – see Sri Lanka.

** For the joys of fan chart analysis, I present to you the IMF’s analysis of Argentina. By design, the fan chart almost always has a downward slope after a crisis (GDP and the exchange rate tend to mean revert) so the IMF can always say that debt-to-GDP is stabilizing and is thus, in a narrow sense, sustainable. The previous Argentina report, back in August (before the latest depreciation):

“The debt fanchart module points to a moderate risk of sovereign stress as in the fourth review. Gross public debt is projected to reach 89.5 percent of GDP at end-2023, around 17 percentage points of GDP higher than projected at the fourth review … Uncertainty as proxied by the fanchart width is significantly lower than in the fourth review (58 vs. 73 percent), indicating that a better aligned real exchange rate could entrench a more positive public debt trajectory. The fanchart index remains at a moderate level (1.87), remaining below the moderate-high threshold. … The overall medium-term index (MTI), which aggregates the debt fanchart and GFN modules, continues to indicate moderate risks. The MTI index is 0.38, consistent with the fourth review. At this level, predictions of stress events will result in false alarms with a 16 percent probability, while predictions of no stress will result in missed crises with a 27 percent probability. Thus, the mechanical signal continues to be of moderate sovereign stress risk …”

Oops.

“The probability of debt stabilization under the baseline continues to be high (around 90 percent). However, given the sharp increase in the initial debt-to-GDP ratio as a result of the step devaluation, uncertainty as proxied by the fanchart width is significantly higher than in the fifth and sixth reviews, which triggers a mechanical signal of high risk of debt distress for the overall medium-term index. However, in staff’s view, the mechanical signal does not adequately capture Argentina’s medium-term risk, as debt-to-GDP ratios is expected to decline rapidly as the overshooting of the REER unwinds and stabilizes at its long-term level and fiscal consolidation accelerates.”

The chart below is from page 67 of the latest IMF report. It essentially shows that the IMF thinks Argentina has a higher probability of having zero debt than increased public debt beyond its current level (if it hits its primary surplus targets). I am not sure that’s really all that helpful of a conclusion.

Technically speaking, the “fan” is a composite indicator of different risks. But composite indicators sometimes obscure rather than clarify. It would be more helpful if the IMF could say clearly that a country’s debt isn’t sustainable because it has too much foreign currency risk, or because it has too much exposure to commodity price volatility. The IMF has consistently overestimated Argentina’s dollar GDP and its sustainable real exchange rate, and its current forecast to me runs the same risk.

*** The IMF insists (see page 52 of its latest review of Sri Lanka’s program) that the restructuring process for Sri Lanka will deliver NPV debt reduction, even at a 5 percent discount rate. But that isn’t actually required by the 4.5 percent of GDP foreign currency gross financing need requirement. IMF and World Bank amortizations appear to be about 1.5 percent of GDP per year, so the 4.5 percent of GDP constraint works out to a limit of around 3 percent of GDP per year in foreign exchange (external debt service). That would seem to allow a 5 percent coupon (NPV neutral) on an external bilateral and bonded debt stock of around 35 percent of GDP. 5 percent of 35 percent – or even 40 percent – of GDP is less than 2 percent of GDP. The program clearly assumes that the bonds and other commercial creditors want more rapid amortization (immediately after the period of limited interest payments specified by the program) and that generates some NPV reduction (though we need to see the details). But nothing in the program forecloses an NPV neutral restructuring with most amortizations left for after 2032. As it is the “NPV” of the external debt stock will start to rise rapidly the moment Sri Lanka starts refinancing its external debt in the market. Think about the NPV at 5 percent of Kenya’s 5-to-7-year, 10.375 percent coupon bond.

**** The low-income country framework, by setting constraints on multiple variables, tends to avoid extremes – one variable tends to bind no matter what. In Zambia’s case, the NPV of debt-to-GDP variables weren’t applied because there wasn’t an agreed GDP number back in 2022 – and that created space for a less constrained outcome as exports are actually quite high relative to GDP. Zambia’s bonded creditors are obsessed about the injustice of the current process, as the official creditors blocked a deal on comparability grounds that the IMF said was OK. They would be in a stronger position if there was a better case than the proposed restructuring terms were actually going to leave Zambia with a sustainable level of debt.

***** The market access country model was actually designed to estimate the risk of fiscal distress in countries that are currently able pay their debts; it was never designed to be used to set targets for a restructuring. Gross financing need is actually a perfectly reasonable variable to examine when estimating the risk of future fiscal distress. And the variables in the market access model for estimating near-term as opposed to medium-term distress are actually quite reasonable. My criticism is limited to using the model for purposes that weren’t part of the original model specifications, so to speak.

Online Store

Online Store