China’s Estimated Intervention in January

It should go almost without saying that China’s ability to maintain its current exchange rate regime matters.

The yuan has been more less stable against the CFETS basket since last July. If the current peg breaks, China will struggle to avoid a major overshoot of its exchange rate.

More on:

Christopher Balding recently has argued that the fall in the dollar (on say the Fed’s dollar index) in 2017 is more or less the same as the yuan’s depreciation against the basket—which would make China’s exchange rate regime now more a pure peg against the dollar rather than a true basket peg. Hence the lack of movement against the dollar in past few weeks. Maybe. I though am inclined to think that the yuan’s depreciation against the basket this year just undid the upward drift against the basket that came when the dollar appreciated last year, and China is still aiming to keep the currency more or less stable against the basket, not stable against the dollar. Time will tell.

![]()

Right now, the exact nature of China’s peg now matters less than China’s ability to maintain some kind of peg, and thus to avoid a sharp depreciation. If there is a depreciation, either the world will absorb a new wave of Chinese exports—a 10 percent real effective exchange rate depreciation should raise China’s real trade balance by about 1.5 percent of China’s GDP, or by roughly $180 billion (using this IMF study as a baseline for the estimate, it is summarized here)—or a wave of protectionist action will limit China’s export response, and in the process threaten the global trading rules.* Neither is a good outcome.

The data for the next few months will be critical. China does seem to have tightened its outflow controls—despite the official denials. FDI outflows certainly have slowed. Hopefully the screws will be placed on a few other categories of outflows—there are plenty of categories in the balance of payments that show a buildup of foreign assets that, in my view, should be controllable. The rise in Chinese bank loans to the world, for example.

I also still think the yuan’s movement against the dollar is an important driver of outflows, so a sustained period of stability in the yuan’s exchange rate versus dollar—whether because the broad dollar is falling and that means the yuan needs to rise to maintain a basket peg, or simply because China starts to prioritize stability versus the dollar—should lead to a reduction in pressure.** Finally China does seem to be tightening its domestic policy, at least a bit. Higher money market rates should also help support the yuan.

More on:

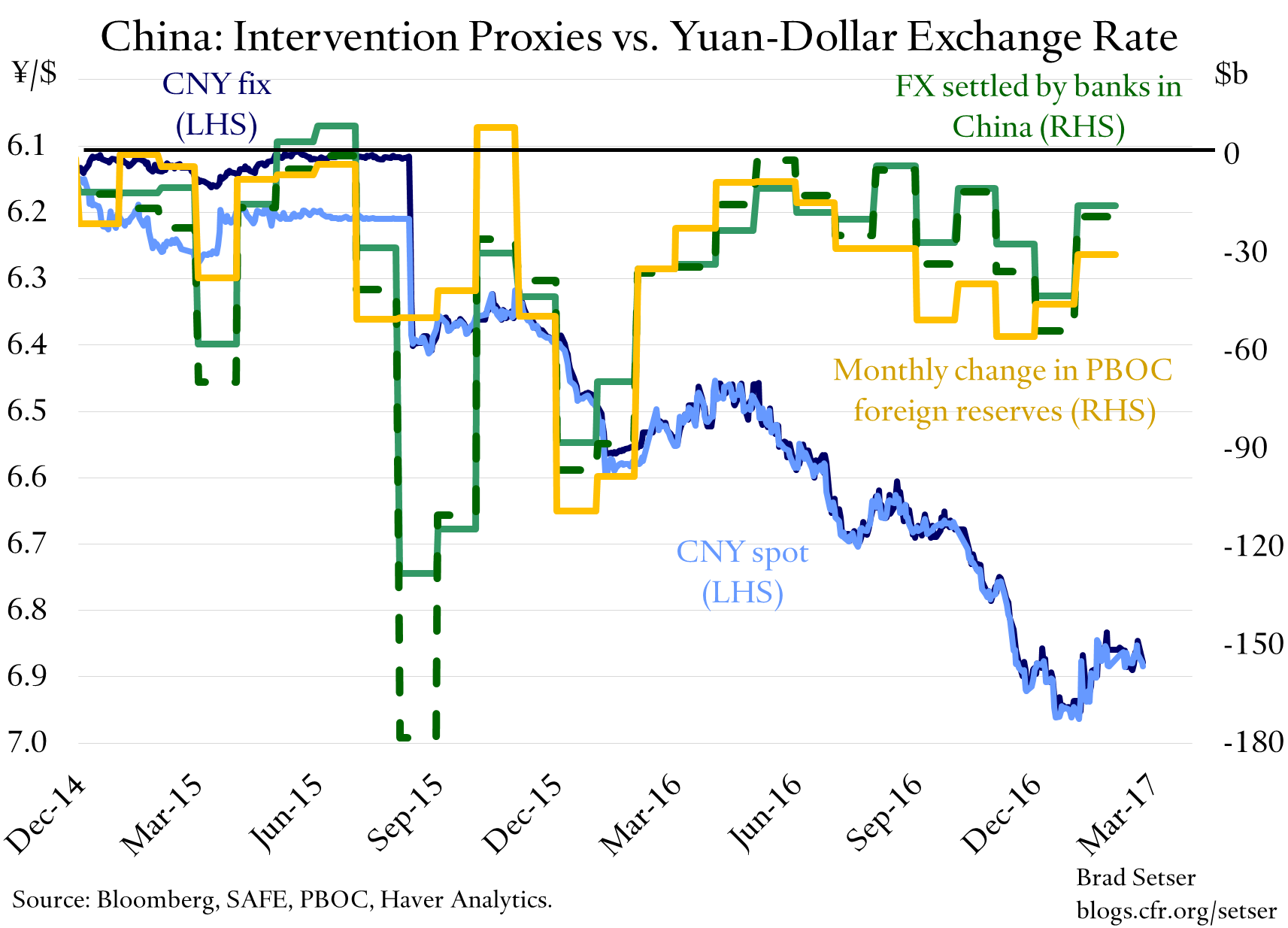

The proxies for intervention for January do suggest some reduction in pressure in January—though pressure by no means entirely went away.

The FX settlement data, adjusted for reported forwards, shows net sales by the banking system of just under $20 billion. That is down from $36 billion in November, and $54 billion in December.

The PBOC’s balance sheet data shows a $30 billion fall in foreign reserves, and a $60 billion fall in foreign assets. That can be compared to an average monthly fall—on both measures—of around $45 billion in the fourth quarter of 2016.

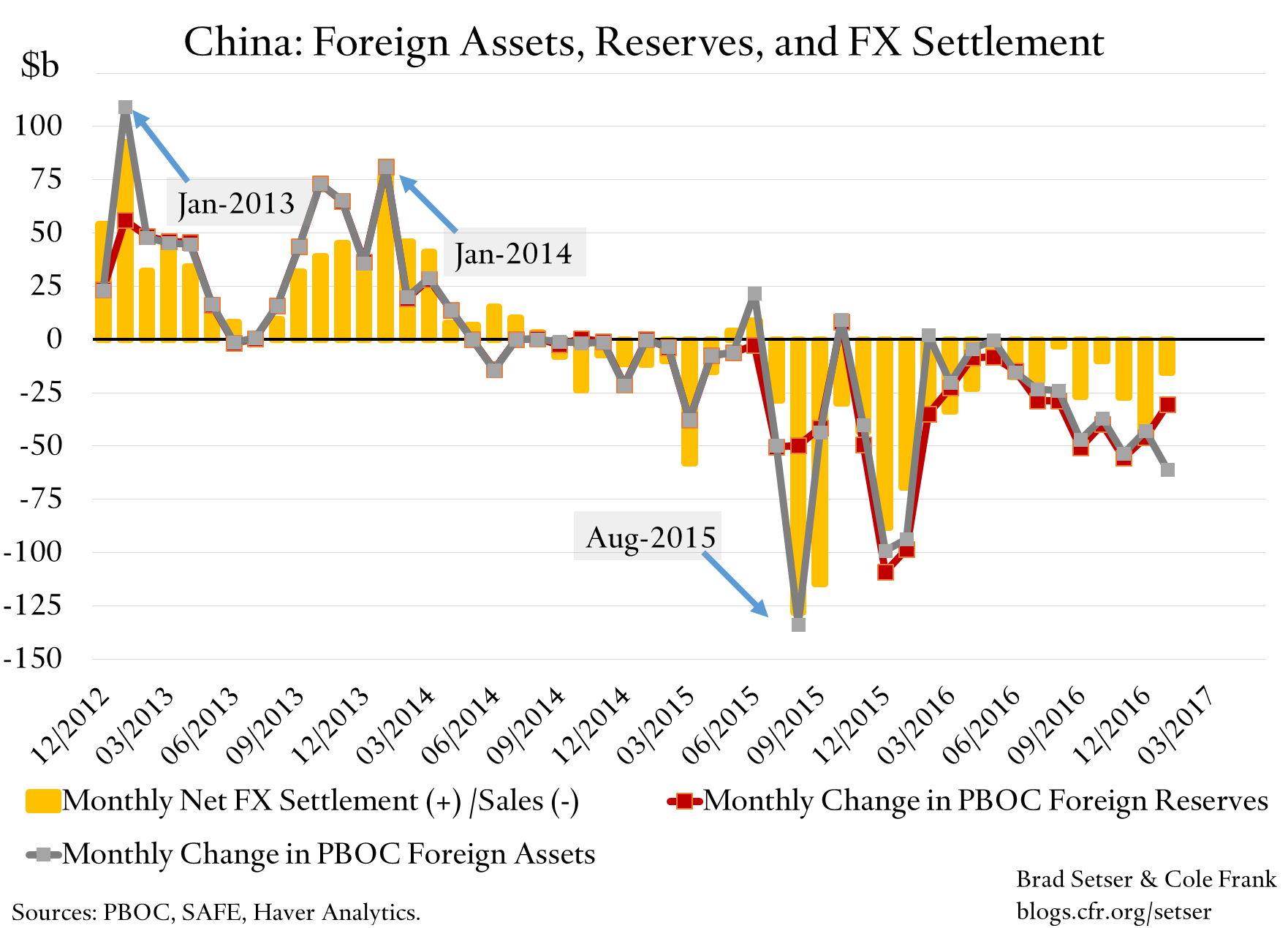

I typically prefer foreign assets to foreign reserves, because foreign assets captures the foreign exchange the banks hold at the PBOC as part of their regulatory reserve requirement—and in the past, changes in the banks required reserves have been a tool that the central bank has used for shadow intervention.

However, the January fall looks to be something else. In the past, changes in the PBOC’s foreign assets—at least those that mapped to backdoor intervention—generally have been correlated with changes in the settlement data (this makes sense, the PBoC’s other foreign assets are in part the banks required reserves, and the settlement data aggregates the central bank and the state banks). One story is that the PBOC has changed how it accounts for its contribution to the IMF.

But until that story is confirmed, the fall in other foreign assets has to be part of the calculus. While the gap between the settlement number and the change in the PBOC’s balance sheet is particularly large in January, a smaller gap has been present for a while. The PBOC’s balance sheet data thus implies slightly larger outflows than the settlement data.

Bottom line: The balance of evidence suggests a moderation in pressure on China’s exchange rate regime in January—but a moderation in pressure isn’t the same as an end to the pressure.

Unlike some, I do not think China’s fundamentals require a depreciation. The current account remains in surplus, China’s export market share has held up well—and China is (once again) growing faster than most of the world. But sustaining the current basket peg will be hard if outflows do not moderate.

* I recognize that a rise in protectionism is a possible outcome even if China doesn’t move

** If stability or appreciation against the dollar doesn’t materially reduce reserve loss over a several month period, I would need to reevaluate my priors

Online Store

Online Store